Demystifying Copyright Law

Under U.S. law, the moment you finish a new work, you are the legal author of that work.

Certain exclusive rights to control the use of that work belong to you.

You don’t need to be an expert in copyright law to understand the fundamentals about your rights. BUT those fundamentals are important.

You may sell, transfer, negotiate limited licenses, or disregard one or more of your “bundle of rights” as you choose. That bundle comprises your copyright rights.

The “Bundle” of Exclusive Copyright Rights

Reproduction

Reproduction: the right to make copies of your work, including copies of some portion of the whole work (e.g., a verse from a song).

Derivative Works

Derivative Works: the right to make new works based on some portion of the original work. Classic examples are spin-offs, translations, and adaptations.

Distribution

Distribution: the right to make copies of your work available to the public. Even if no money is involved, only you can authorize distribution.

Public Performance

Public Performance: the right to perform works like scripts, songs, movies/videos, and choreography in a place open to the public (beyond just friends and family). The performance can be in person, like concert, or via transmission, like radio, TV, or the internet.

NOTE: There are lots of special rules for Sound Recordings, which have a more limited public performance right and does not include radio broadcast.

Public Display

Public Display: the right to show a work at a place open to the public (again, beyond friends and family). This right typically applies to works you look at (e.g., photos, illustrations, paintings, sculptures). This is a big one because there is a LOT of display online. Note: if/when you find your work displayed online, it may be necessary to figure out which website is actually hosting the image.

Public Performance by Audio Transmission

Public Performance by Digital Audio Transmission: only for sound recordings, this basically means the right to stream those recordings for the listening public.

Duration of Copyright

For any work created by a U.S. citizen after January 1, 1978, the term of protection is the Life of the Author Plus 70 Years. For older works, works created by non-U.S. citizens, and older published works (and which may also be non-U.S.), the duration thing gets a little complicated to summarize. Such instances may require some research with the help of a qualified attorney. But don’t let people on the internet tell you it’s already in the public domain because it might not be!

Anonymous and pseudonymous works, and works made for hire (WMFH) are protected for a term of 95 years from date of first publication or 120 years from date of creation.

NOTE: Although we strongly urge everyone to register work as soon as possible after it’s completed, a post-1978 work may be registered with the Copyright Office at any time during its term of protection.

The right to control the use of your work does not depend on money changing hands.

A use without permission need not be commercial to be infringing.

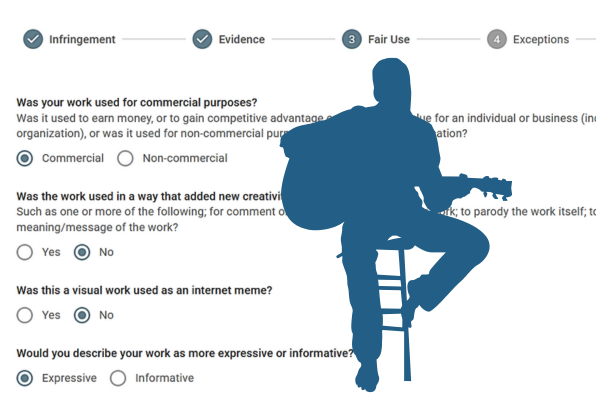

Fair Use

Copyright rights are important and powerful, but not absolute. If someone copies a word or a phrase from a book, that’s probably not an infringement. Likewise, they may take more than that but if it’s for a socially beneficial purpose like news reporting or nonprofit education, it still may be allowed without the permission of the copyright owner. The Fair Use doctrine is designed to allow uses of copyrighted works when they benefit society but do not harm the financial interests of the copyright owner too much.

Fair use cases are notoriously hard to predict. It’s not just a matter of adding up the factors and seeing who has more on their side. And the four factors are just the minimum a court must consider – it can also consider other facts it thinks are relevant.

As a general matter, commercial/profit-generating uses are less likely to be considered fair use, while nonprofit uses like teaching, comment, or criticism are more likely to be considered fair use. Courts will also consider whether the use is “transformative,” meaning that the new use in some way comments upon the work used. While debate may linger as to what “transformative” means, the need to comment upon the work used is guidance recently provided by the Supreme Court.

Copyright protects creative expression, so the more creative a work is, the more protection it typically receives. Thus, the use of fictional works, music, paintings, etc. generally weighs against fair use. Works with extensive functional or factual elements, like computer code, scientific papers, and nonfiction works generally receive narrower protection, and use of these works more often favors fair use.

The more of the original work that is used, the more likely it is that this factor weighs against fair use. Note that this is both about the quantity used, as well as the importance of what is used. For instance, copying the “heart of the work,” even if it is perceived as a small amount of the whole work, will weigh against fair use. One myth you should not believe is that there is a fixed percentage of a work that always favors fair use.

Think about this one this way: if everyone used the original work in the same way, would people still want to purchase/license the original work? Of course, the more harm to the market for the work, the more likely this factor weighs against fair use.